Interest rates have gone up the past few years, by a lot. That could be a bad thing if you’re looking to buy a house and need a mortgage. Or it could be positive if you are enjoying a higher interest rate on your bank deposits for the first time in many years. Where interest rates go from here is a topic of hot debate currently, particularly with a presidential election later this year. Many market watchers expect interest rates to come down, and indeed, the Federal Reserve has indicated it expects to cut short-term interest rates in 2024. However, we’re not so sure.

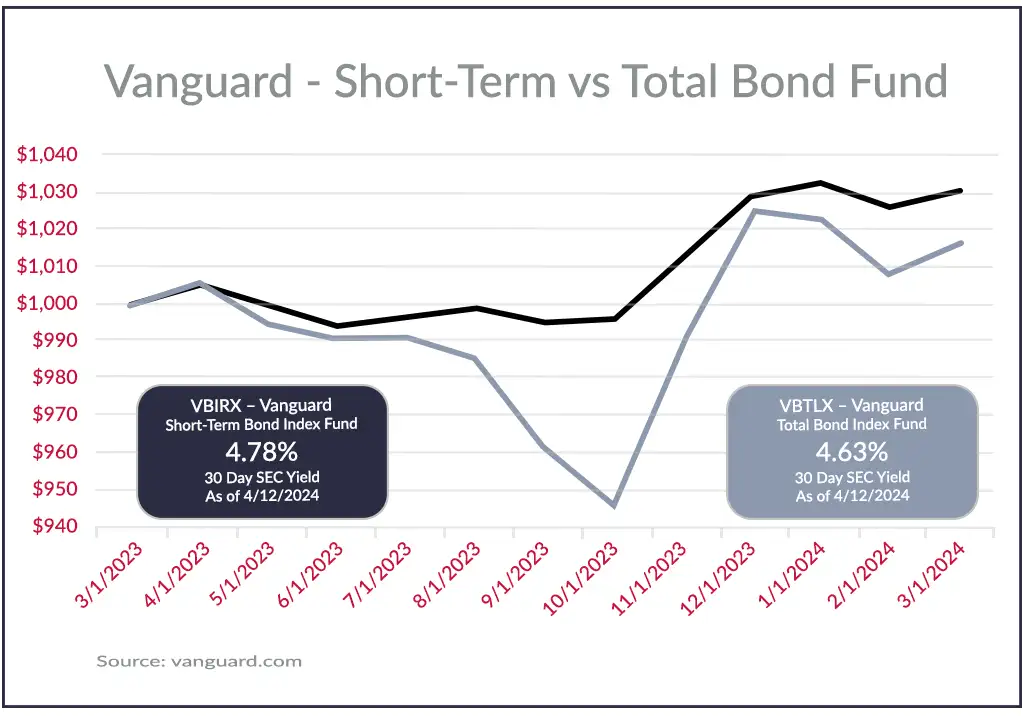

If interest rates do come down, we would want to be in longer-term bonds. Interest rates and bond prices move inversely to one another, and long-term bonds are more sensitive to interest rates moves. That means you could potentially generate big returns with long-term bonds if the Fed cuts rates. We currently use short-term bonds since their return hasn’t been much different from long-term bonds, and they incur less risk. In fact, by way of example, Vanguard’s short-term bond index fund currently has a higher yield and better performance over the past year than the Vanguard long-term total bond market index fund (see chart below).

Vanguard Short-Term vs Total Bond Fund – VBIRX vs VBTLX

Many pundits, economists, and Fed watchers are recommending investors lengthen the duration of their bond portfolios to take advantage of the expected rate decline. We disagree. We may miss out on a bit of performance if rates do indeed drop from here, but we’re skeptical that rates will come down much, if at all, in both the near and longer term.

That may sound odd since the Fed has been saying it will cut short-term interest rates this year. However, in our view the Fed’s credibility isn’t what you might like it to be. Last year the Fed told us inflation was “transitory.” Inflation is still a problem. In fact, core inflation is almost twice the Fed’s target rate, despite coming down quite a bit from last year. There have been studies comparing the Fed’s economic forecasts to those of private sector economists, and the Fed has generally fared better. However, that still doesn’t instill a lot of confidence when you consider the accuracy of private sector forecasts. Some studies have found that economists, market watchers, and political forecasters were accurate only 47% of the time; less than flipping a coin. So, just because the Fed says it is going to cut interest rates later this year as inflation comes down and the economy remains robust, it doesn’t make it so.

Also, even if the Fed does cut interest rates, it doesn’t necessarily imply that longer-term interest rates will decline. These are the rates that truly matter for bond market pricing. There has been a strong historical correlation between the short-term Fed Funds rate and the longer-term 10-year Treasury rate, but it isn’t perfect and there have been wide divergences in the past. It is certainly conceivable that if the Fed rushes short-term interest rate cuts, it could spur even higher inflation, which could lead to a sell off (and rate rise) in longer-term bonds.

The Fed says it is watching “the data” to determine what it will do in the future. That data includes inflation, GDP growth, unemployment rate, industrial production, and many others. Recently, most of these indicators have shown a strong economy. We can certainly quibble about the quality of the data and whether part-time job creation is the same as full-time job creation, but the full mosaic shows solid economic growth. That means the Fed won’t have any true impetus to trim interest rates in the near future.

Longer-term, we don’t think the outlook is that bright for continued economic growth, given the huge government debt both in the US and overseas, uncontrolled inflation, unfavorable demographic trends, a declining appetite for Treasury bonds among foreign nations, and what will almost certainly be declining corporate profitability that could lead to larger scale job loss. These things, if they get out of control, could lead the Fed to trim interest rates. However, we’re still not convinced that will happen in any meaningful way.

The real problem is that inflation is persistent and doesn’t appear likely to abate anytime soon. Inflation seems widespread. Housing prices continue to rise and there is no catalyst for them to decline given a shortage of housing stock and regulations discouraging building in many parts of the country. Commodity prices including oil, copper, and gold have all increased meaningfully in the past few months. And wage increases finally starting to catch up with core inflation. While inflation has come down from its blistering pace last year, these factors make it less likely that it will fall further, and we wouldn’t rule out another spike, just like what happened in the 1970s.

Because of that inflation, and the risk that it could go even higher, we don’t think the Fed will be able to meaningfully reduce interest rates any time soon. Moreover, longer- term interest rates have historically trended in long cycles ranging from 25-40 years. It seems we just finished a 40-year cycle of declining interest rates when the 10-year Treasury yield hit 0.5% during the Covid downturn. It won’t be a linear rise, but rates could trend higher for the next couple decades or more if history repeats.

There are a host of other risks that could push interest rates higher, such as a significant weakening of the US dollar, even a small decline in demand for Treasury securities as their supply continue to rise with profligate government spending, or on the bright side a further strengthening of economic growth. But there are also forces that could push rates down, including a financial crisis or a politically motivated cut before the election in November. Just like timing the stock market, it is impossible to know for sure where interest rates will go. But because there is so much risk currently in being wrong, we’ll continue to use short-duration, high credit quality bonds. Stocks are in the portfolio for growth, but bonds are there for safety. Even if we give up a little performance in the short term, we’d prefer to keep our bonds extra safe.